Your agents need runbooks, not bigger context windows

Why Your AI Agents Need Operational Memory, Not Just Conversational Memory

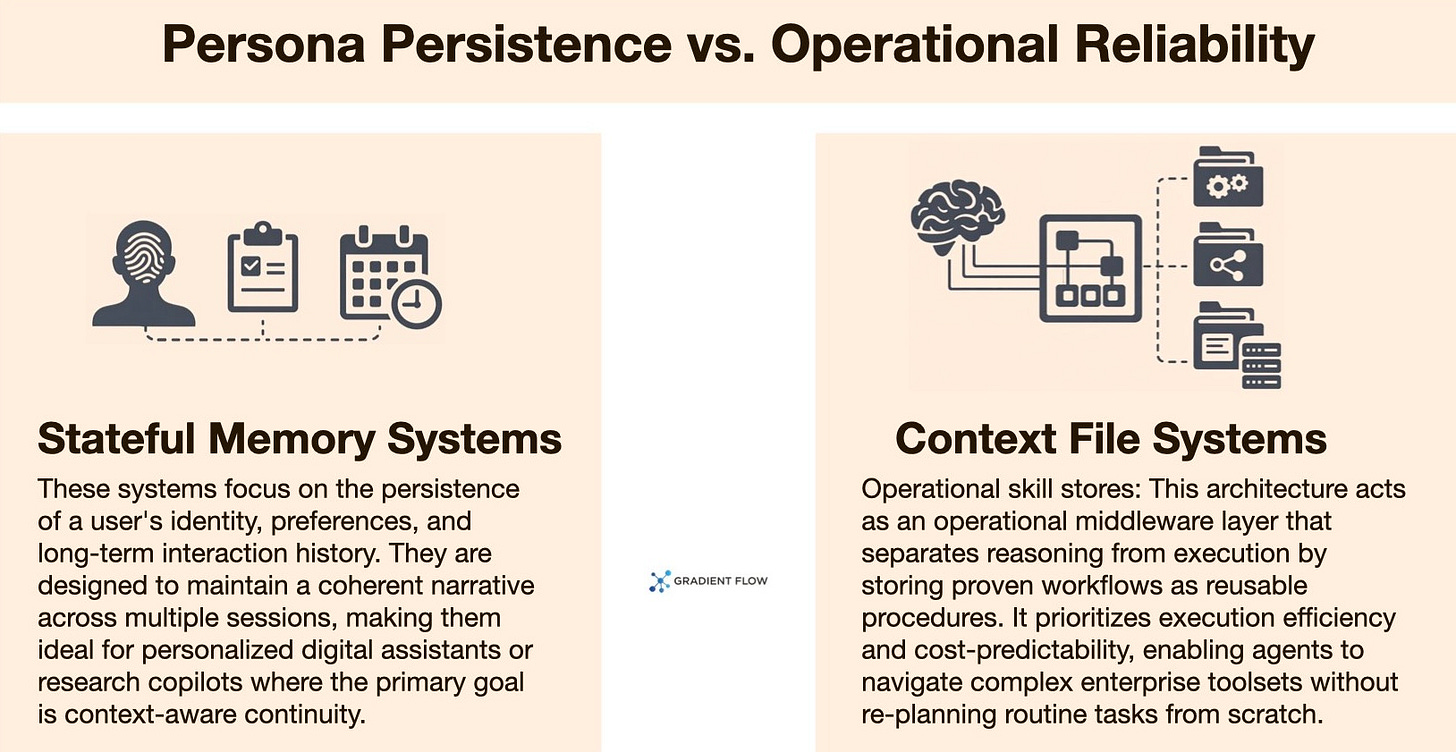

Now that AI agents are moving out of the lab and into the real world, we’re realizing that “memory” isn’t one-size-fits-all. Most people think of agent memory like a personal assistant. It remembers your preferences, your travel plans, and the email you composed last week. This is great for a research copilot or a personal coach where the goal is a long-term relationship.

But if you’re deploying agents to handle back-office operations like fixing data pipelines or managing APIs, you don’t need a persona. You need reliability. I started looking into this because I saw teams struggling to make agents work in high-stakes, repetitive environments. In these cases, the goal isn’t conversational flair. Instead, it’s making sure the agent doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel every time it performs a task. By separating how an agent “thinks” from how it “acts,” we can finally scale automation without the massive costs and unpredictability that usually come with it.

Constraints of Infinite Context and the Limits of Modern Transformer Architectures

In a production environment, the "just add more context" strategy hits a wall very quickly. Even though context windows have grown massive, the math behind them is still expensive. Because computational work grows quadratically with input length, the more information you dump into a prompt, the slower the agent gets. A task that should take one second can balloon into thirty seconds just because the context is too large. There is also the “lost-in-the-middle” effect to worry about. When prompts get too long, agents often lose track of the information buried in the center. Research shows that giving an agent small, focused snippets is often twice as accurate as making it read a giant document.

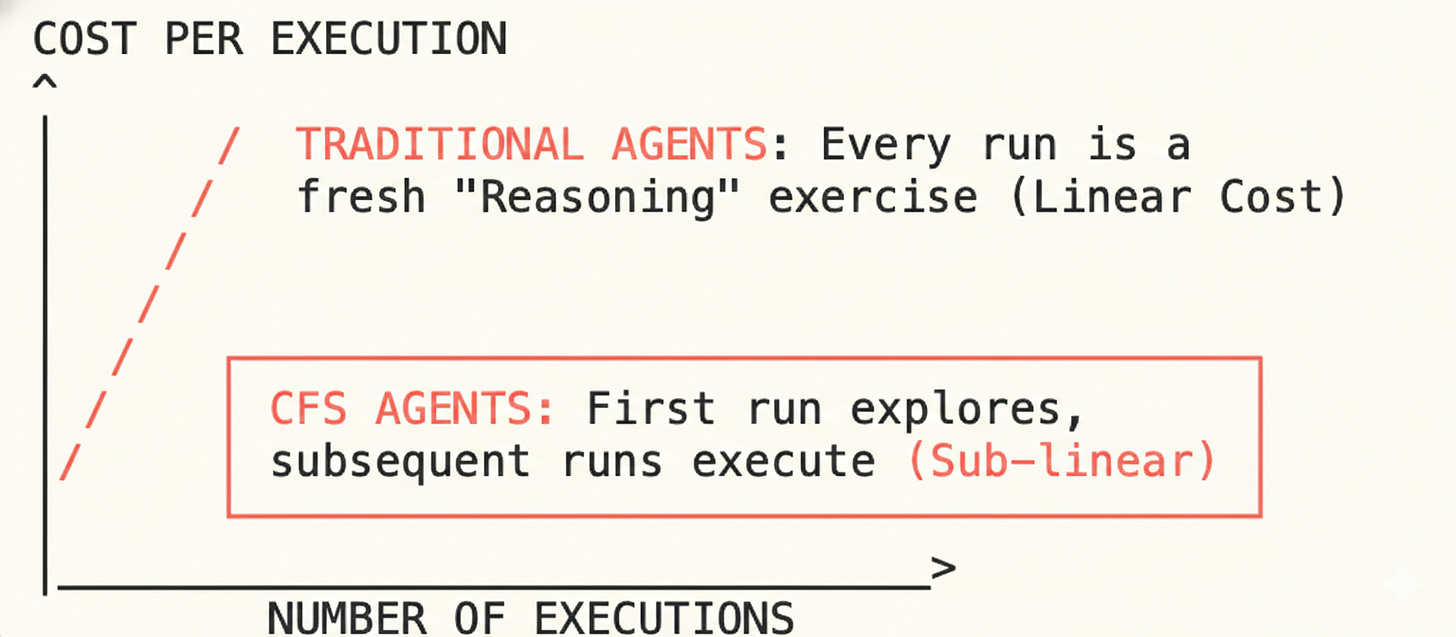

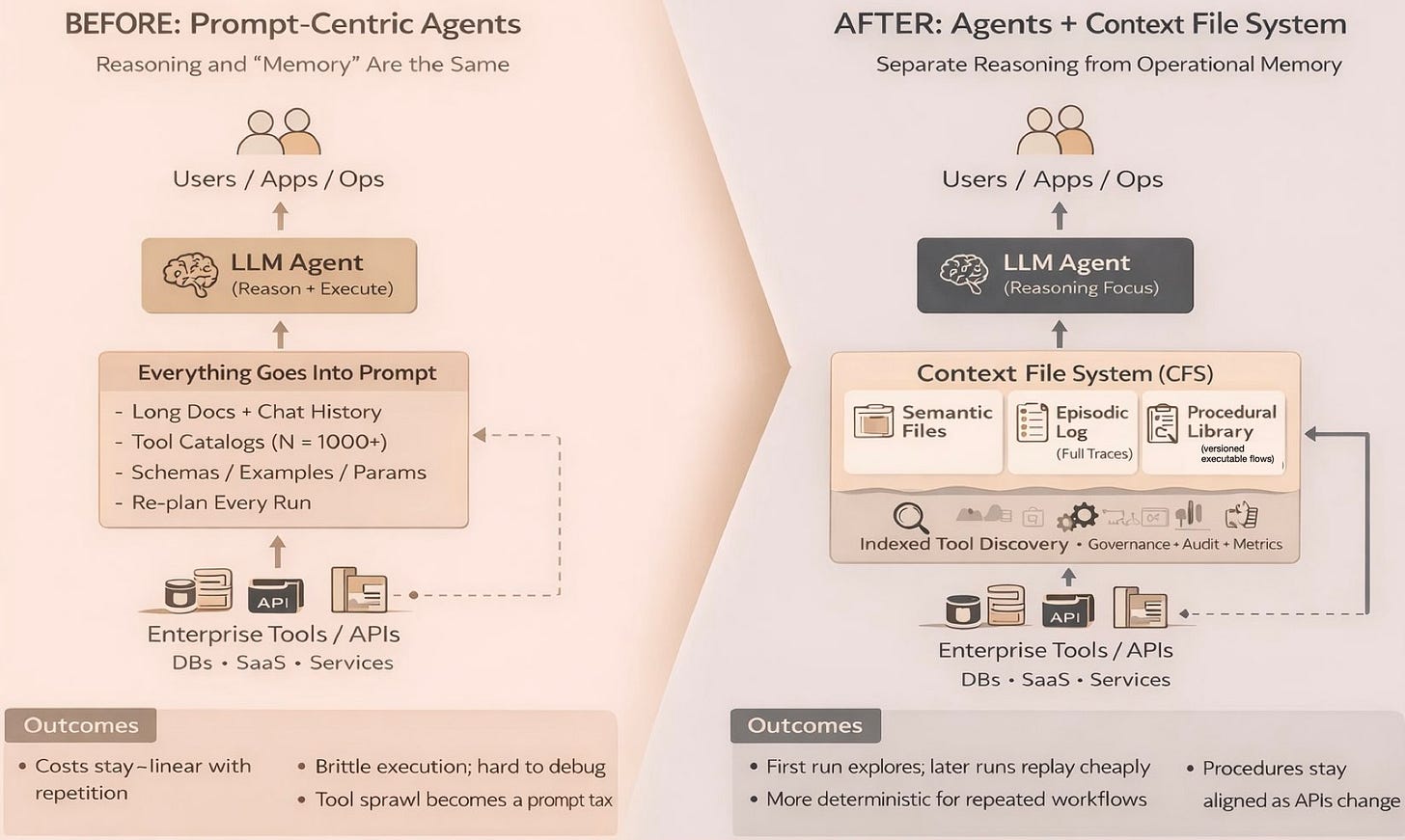

Beyond the technical overhead, there is a structural problem with how agents handle enterprise infrastructure. If you have hundreds of internal tools and APIs, describing them all can eat up your prompt’s token budget before the agent even starts its work. Most importantly, today’s architectures don't allow for organizational learning. Every time an agent runs a task, it treats it like a brand new puzzle. It pays the full "thinking cost" of planning and discovery every single time. Without a way to save and reuse a successful workflow, the system never gets faster or cheaper. It just stays stuck in a loop where the 1,000th execution is just as difficult as the first.

The root of this problem is that we are treating the agent’s context window like RAM: a volatile workspace that wipes clean the moment a task is finished. In a traditional computing stack, you wouldn’t reload your entire operating system every time you wanted to open a text file. But in the current agent paradigm, we force the model to “re-boot” its understanding of our infrastructure for every single request. This creates a massive Context Tax — a recurring overhead where you pay in both latency and tokens to re-teach the agent things it should already know.

The Attention-Window Workarounds: Current Memory and Context Architectures

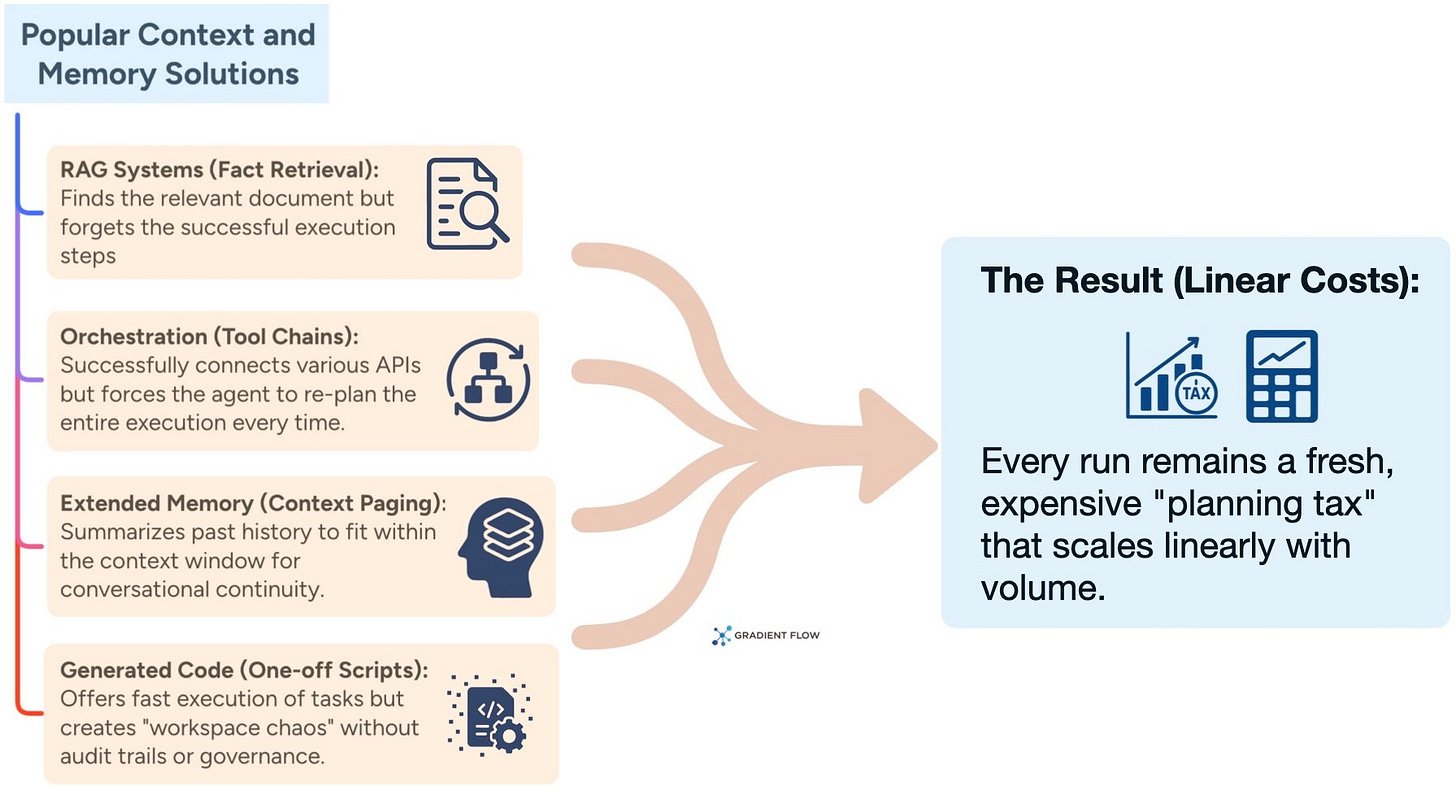

Most current ways of handling agent memory focus on finding information rather than reusing successful actions. Take Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) for example. It is great at fetching facts to help an agent answer a question. This helps avoid the "lost-in-the-middle" problem. But RAG is built to find documents and not to remember how a job was actually done. It can find a technical runbook for you. However, it cannot remember that a specific five-step sequence of API calls fixed a database issue last week. Every time a workflow starts, the agent has to read documentation and plan its steps from scratch.

More advanced agent orchestration frameworks try to fix "catalog bloat" by loading tool definitions only when they are needed. This saves money on tokens, but it still doesn't help the organization learn. Other systems focus on "stateful continuity." This ensures an agent remembers who you are and what you like over several months. That is perfect for a personal assistant, but it doesn't help with operational tasks. If an API is broken or a tool description is confusing, the agent will just keep making the same mistake every time it runs. We also see agents that write code on the fly. This often leads to "workspace chaos" where you end up with hundreds of one-off scripts that nobody has verified or tracked.

In the end, current memory methods force agents to remain in a state of perpetual improvisation. Because there is no way to “crystallize” a successful solution into a reusable procedure, the organization never develops an institutional learning curve. To really scale in an enterprise, agents need to stop just managing what is in their immediate context and start building a permanent library of proven procedures. This transforms one-off successes into reliable, repeatable assets.

The Context File System: Memory for How Work Gets Done

To fix these structural bottlenecks, we are seeing the rise of what dex calls a Context File System (CFS). You might also hear this more broadly categorized as an Operational Skill Store. This architecture separates the expensive reasoning of a large language model from the actual storage of operational knowledge. It mirrors the way a mature engineering team works. Senior staff solve a novel problem once and then document the solution in a runbook so the task becomes routine. By turning successful executions into permanent and reusable procedures, a CFS transforms agents from improvisational tools into reliable enterprise infrastructure.

This architecture shifts the role of the context window from a temporary, volatile buffer to a persistent storage layer. Rather than stuffing a prompt with “just-in-case” information, a CFS allows the agent to “mount” and “unmount” specific operational volumes as needed. For example, an agent can mount a specific codebase volume to understand a bug, then swap it for a technical runbook volume to execute the fix. This “Context-as-a-Service” model ensures the agent’s focus is always high-density and low-noise, treating context as a managed resource rather than a fleeting byproduct of a conversation.

This approach fundamentally changes the economics of AI. In traditional systems, the 1,000th execution of a workflow costs as much as the first because the agent has to re-plan the task from scratch. With a CFS, the first execution pays an "exploration cost" in tokens. Every run after that simply replays the proven procedure. This often reduces token consumption by over 90 percent. It also solves the problem of "tool sprawl." Instead of stuffing a prompt with hundreds of API definitions, the CFS indexes these capabilities externally. It only loads the specific documentation required for the task at hand. This ensures that agents remain fast and accurate even as your company infrastructure grows in complexity.

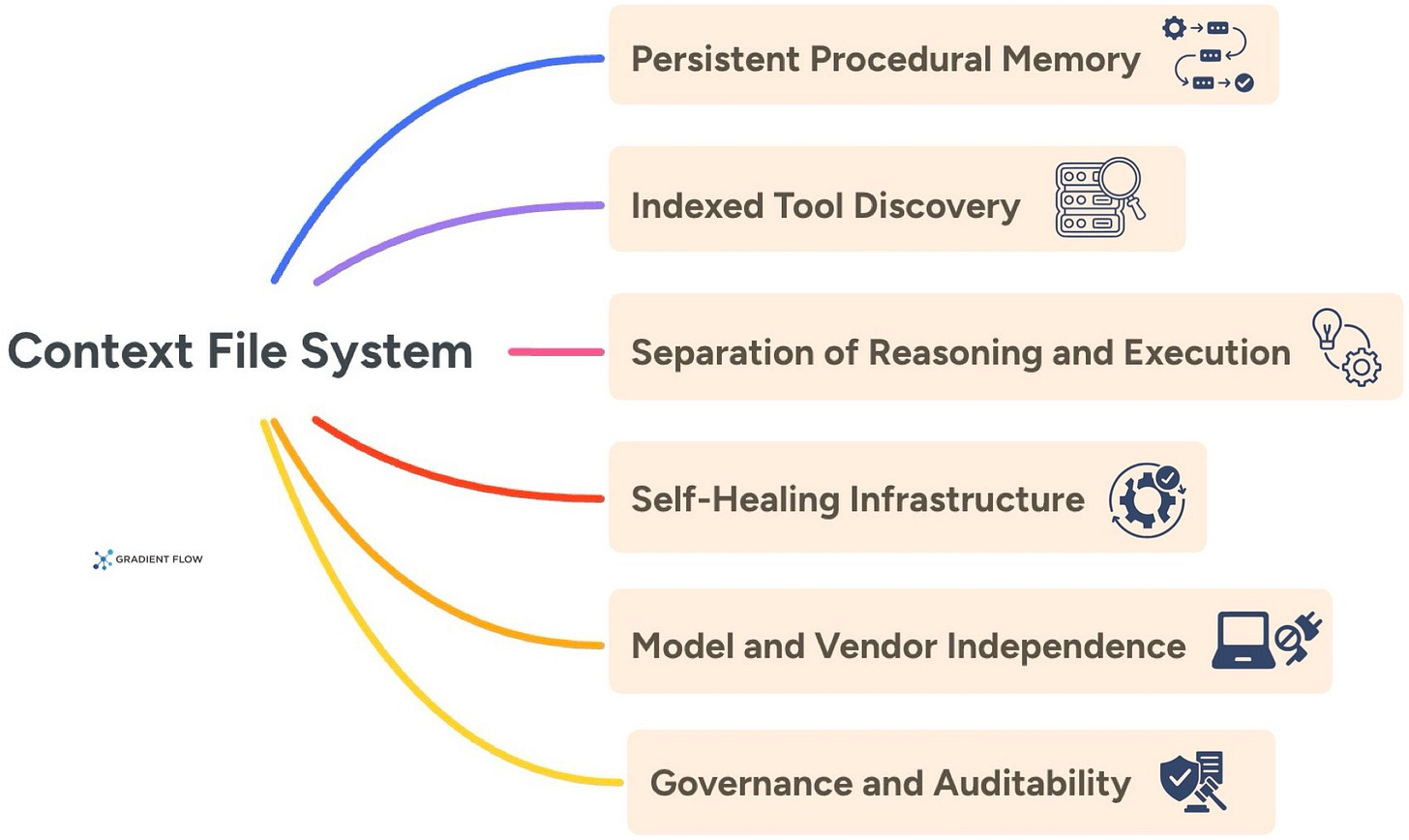

A Context File System or operational skill store is defined by a few key features:

Persistent Procedural Memory. Successful multi-step workflows are captured as versioned and executable procedures. These can be reused across the organization to eliminate the need for repeated planning.

Indexed Tool Discovery. Rather than forcing an agent to memorize a massive tool catalog, the system maintains an external index. It only exposes relevant API schemas when they are actually required for the current task.

Separation of Reasoning and Execution. High-cost model reasoning is reserved for genuinely new problems. Routine work is handled by the memory layer instead. This shifts the cost curve so that the system gets cheaper as usage scales. You stop paying for the model to “re-reason” through a solved problem, effectively turning a variable cost into a fixed, reusable asset.

Self-Healing Infrastructure. The system monitors the success rate for every learned procedure. If an underlying API changes and a workflow begins to fail, the system automatically pulls the procedure and triggers a re-learning phase.

Model and Vendor Independence. Procedures are stored as standard executable code rather than proprietary prompt formats. This allows your organizational knowledge to remain portable even if you switch AI providers.

Governance and Auditability. Every action is recorded in an episodic memory layer. This provides the full execution traces and version control necessary for debugging in regulated environments.

Beyond immediate cost savings, the CFS provides a way to compound organizational value. Knowledge gained by one agent execution becomes an immediate asset for the entire enterprise. This creates a self-maintaining model that adapts to changing infrastructure without requiring manual prompt engineering. It allows AI agents to function as a stable and scalable part of the modern software stack.

Roadmap for Operational AI and Enterprise Agent Deployment

The future for Context File Systems like dex points toward a central hub. This is an internal registry where a workflow discovered by one team becomes instantly available to the whole company. In this model, a successful solution becomes a company asset that is versioned and governed just like standard IT code. Future versions will likely have better self-healing capabilities. They will be able to tell the difference between a temporary network error and a permanent change to an API. This evolution turns AI infrastructure from a series of isolated experiments into a library of expertise that gets more cost-effective as it grows.

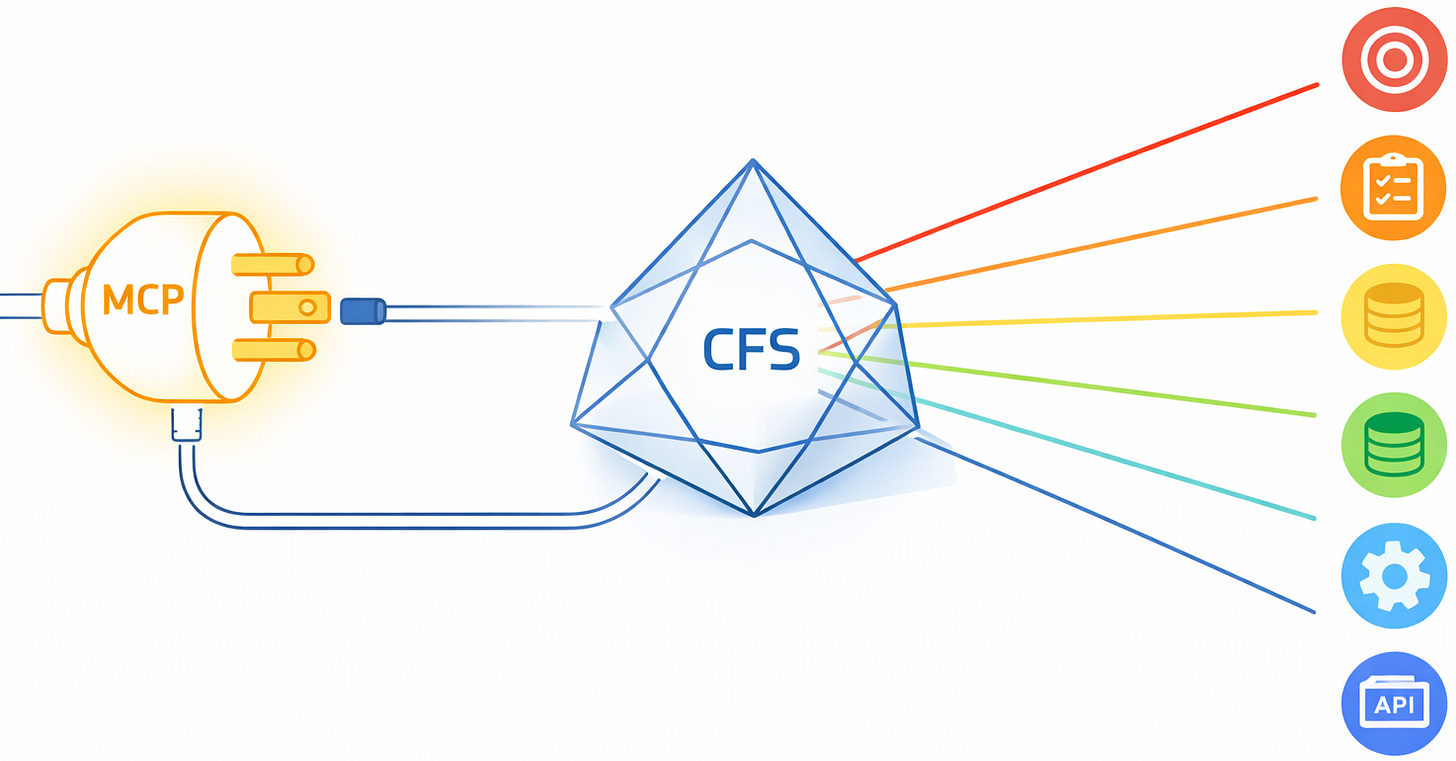

For AI teams, the relationship between a Context File System and the Model Context Protocol (MCP) is a foundational choice. While MCP provides the standardized plug that lets agents connect to internal systems, a CFS acts as the layer that makes that connection economically viable. Without a CFS, a large-scale MCP deployment risks falling apart under the weight of its own tool catalog.

Organizations should prioritize stateful memory systems when the main goal is conversation and personalization. This is perfect for research copilots or personal assistants. On the other hand, a CFS architecture is the better choice for high-repetition operational work like DevOps automation or data engineering. In those environments, the goals are cost predictability and the reuse of proven procedures.

Quick Takes

Ben Lorica edits the Gradient Flow newsletter and hosts the Data Exchange podcast. He helps organize the AI Conference, the AI Agent Conference, the Applied AI Summit, while also serving as the Strategic Content Chair for AI at the Linux Foundation. You can follow him on Linkedin, X, Mastodon, Reddit, Bluesky, YouTube, or TikTok. This newsletter is produced by Gradient Flow.